Stueland's agenda includes an investigation of how the language used to represent climate changes influences our attitudes and behavior. He poses the question: What language do we use when we talk about the nature and environmental challenges? Stueland considers this question in relation to a wide range of discourses: everyday language and experiences; research-based facts; wording and actions in the fields of politics, economics and business life; and representations of nature in the arts and literature.

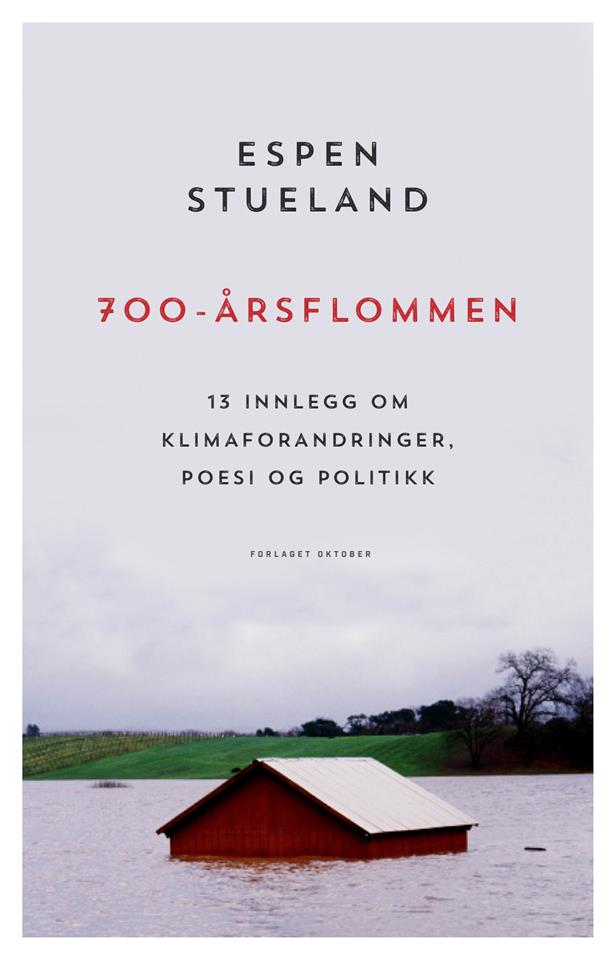

The book title refers to a term used to denote the scope of a major flood in Western Norway in October 2014. One of the book’s most captivating passages describes Stueland’s own experiences related to this flood in his hometown Voss (ch. 2). On his way home from his daughter’s football practice, he suddenly finds the road flooded with water, and terrified, he watches his daughter disappear into the flood waters a few meters in front of him. She escapes, but they have to leave her bike behind in the water. This scene, combined with other reports and issues regarding the flood, accentuate the urgency of Stueland’s engagement in the climate debate.

Stueland considers the humanities and social sciences to be as important as the natural sciences in the climate discussions, and he refers to debates and research in all these fields. The style and topics chosen are influenced by Stueland’s experiences as an author of poetry, novels, essays and literary criticism. Throughout the book, he introduces poetry by various authors to highlight discussions of environmental issues. His reflections also have a political agenda. Stueland sees a need for a policy that will allow substantial adjustments to be made in order to meet the environmental challenges of today and the future.

The book’s five last chapters emphasize the writing and reading of literature from an ecocritical perspective, and they are of particular interest to the NaChiLit research group. Stueland poses the question: In what ways can literary texts foster ecocritical consciousness? He provides an extensive introduction to, and discussion of, ecocritical theories, supplemented by ecocritical readings of literature. Examples include a study of what he calls toxic poems by authors such as Inger Christensen, Olav H. Hauge and Adam Dickinson; discussions of dystopian and (post) apocalyptic literature, largely based on Theis Ørntoft’s ecopoetry in Digte 2014; reflections on how to review ecocritical literature; and a reading of poems by Tor Ulven in light of deep ecology theory.

The way Stueland brings literary texts into his multifaceted exploration of environmental issues is thought-provoking. Ultimately, the reader is captured not by fixed answers, but by the sincere questions raised regarding how to respond to the urgent climate issues of our time.

Berit W. Bjørlo 01.03.2017